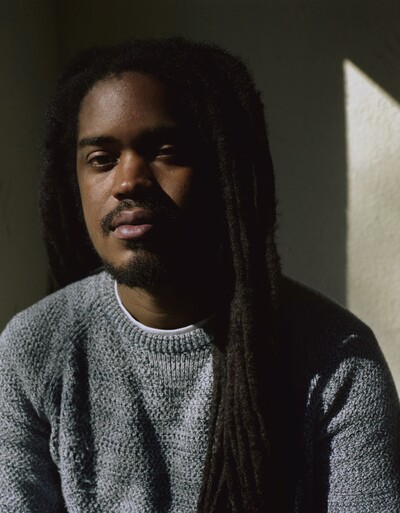

Julien Creuzet in conversation with Andras Szántó

EVERY MOMENT IS IMPORTANT

WHEN YOU LOSE WHERE YOU ARE FROM, YOU ARE NOBODY ANYMORE

WE NEED TO THINK ABOUT HOW TO HAVE A NEW VISION

THE CARIBBEAN MUST BE A SITE FOR EXPERIMENTATION

AS: This is the first Art Journey where an artist is heading home. What does home mean to you?

A good question to start. Home for me is about the heart, and the heart is about the imaginary and emotion. The first emotion you can have about place is where you feel good, a place you feel connected with. For me, this place is Martinique Island.

I was not born there—I was born in a suburb of Paris—but I lived there from age 4 to 20. I studied at university in France, in Normandy. After graduate studies in art and cinema, I arrived in Paris, maybe 15 years ago. Over the last decade, it was difficult for me to return to my home for many reasons.

AS: Why did you decide at this stage in your life to return to Martinique, a place where have never worked as an artist and have never shown your work?

We live in a strange moment, with COVID and quarantine. You had to ask yourself, what can we do? What is the necessity of our jobs? All museums were closed. Art was not a first necessity, even for a huge city like Paris. Culture was not a necessity. We need to think about why—what bad choices did we make in the past that led to today, where people don’t understand culture and art as a necessity?

For me, that is a very important question. In the contemporary art world and art market, people were traveling to different places all over the world. The art works got expensive. But now that is in the past. It is the old world. Now, we need to think about how to have a new vision.

During quarantine, I asked myself, how can my work have a necessity for communities? I would like to put forward a more ethical position in my work. For me, it is important to go to Martinique, because it is an island. It is far, and isolated. It is hard for people to live there. They do not have money. There is no opportunity to go to a museum or show their works in an art space or a gallery. We need to ask, through what initiatives can the public have a connection with the ideas and concepts an artist shares?

Now is the moment, with the help of BMW, for me to go to Martinique—to reconnect with this island and these communities, to create an experimental station; a space of freedom and safety, with generosity. It’s an important possibility for me to share my energy, too—what I have learned during the last fifteen years in a different part of the world—and to share my vision. All this is a way of saying: It is possible to be an artist and work in Martinique.

AS: Another poet from Martinique who once lived in Paris was, of course, Edouard Glissant. He, more than any writer, gave expression to the idea of the Caribbean. It’s impossible to miss this parallel. To what extent is your project inspired by Glissant?

Edouard Glissant had a vision of the future. It is optimistic and positive about the future, trying to understand how it is possible for us to live together. For me, for example, it is necessary now to think about how we can share water and food between the continents over the next fifty years. There is an urgency now not to lock the borders. The thinking of Edouard Glissant helped me understand how we can have a long perspective, and that we are not alone in this earth. We need to live together.

I have done research about Haiti and how the population has this power to stand up every day after great tragedies. Now is a moment to say, I am not alone. And when I start to work, to invent with musicians and choreographers, with writers, with designers – I am never just me producing my work. Think about the cinema. For a single movie there may be three hundred people working together on the same project. You need all this energy. For me, an exhibition is the same. It’s like an opera. It is about a total experience.

The same way, I need to understand how to be more comfortable in my body and in my head. I want to share my ideas about sculpture. Now, with BMW, I have an opportunity to start this process towards my vision for the future. Through movement, I want to make more connections, to try to connect what happened in the Caribbean and in all the French colonies, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Madagascar, and other places.

AS: One of my favorite of Glissant’s terms is mondialité – this idea that our differences are not a bad thing, but to the contrary, a positive thing to turn into something beneficial. This is the first Art Journey entirely based in the Caribbean. What does the Caribbean mean to you? What does it teach us?

The Caribbean is an archipelago. Every island is connected by the ground inside the water. When one volcano in Martinique wakes up, the volcanoes of the other islands start to move as well. You have a connection.

But the ecosystems on each island are different. For example, in Martinique you have specific trees that you will not find on other islands. Each island is unique, each has a specific history. Guadeloupe and Martinique were French colonies, but it is not the same place—even a one hundred-kilometer distance can make a difference. In Martinique, the French Revolution didn’t happen, because France gave the island to England. And now, in the present, you can still feel what happened two hundred years ago.

You need to understand colonization and the African Diaspora to understand the Caribbean. People in the Caribbean are from everywhere in Africa. We mix English with Portuguese; with Spanish; with Yoruba; with ancestral languages from Africa; with Carib; with Arab languages. All of that has created a very interesting culture. But for me, preserving that culture is not the goal. I am afraid of tradition. I’m afraid when we stop cultural processes. The Caribbean must be a site for experimentation.

AS: Your BMW Art Journey is about going to Martinique and engaging with young people, schools, and creatives, to build what you call an ephemeral studio. Can you describe in more detail what you plan to do?

It will be an experimentation station. Think of what Theaster Gates has done on the South Side of Chicago. There are two things I want to do. I would like to use the Martinique context to create fiction using the different parameters of society. In the same way, I would like to create an artist-run space where we can invite different people.

How can we do that? It could look like a BMW pavilion in Martinique, for a moment. That is my dream. It can be a living place. I would like it to be a space where people can have a performance, a public discussion, a short exhibition, and so on. There could be a studio to produce new artwork. It is important to me to be in Martinique and to be able to use specific objects and materials found in this place, which I have never had the ability to do. I would also like to create workshops and have discussions with students and invite them to participate in different artworks, or something like a Carnival.

AS: I understand the impulse to go deep. Many journeys, especially touristic ones, are superficial. They are quick encounters. Now you are trying to drill down into the deeper layers of a culture. Can you tell me more about the cultural life in Martinique?

The slave trade stopped in Martinique in 1848. The first art you can identify from this moment is dance. Dance was really important, and so was music and storytelling. In Martinique, we call storytellers raconteurs. To me, those were the first forms of “art” in the Caribbean. Don’t forget, the Caribbean has a specific ecosystem, with 99 percent humidity. You know what happens with paper with aquarelle in 99 percent humidity. So, we need to adapt what art is and what art can do, and how it can perhaps be more ephemeral.

Martinique became a French jurisdiction in 1946. That was the first time all children could have an education. The children could now imagine becoming a doctor, a lawyer, a teacher, and learning other languages, going to university. Only then could people start making art like we can imagine. But for a long time, artists from Martinique did not have opportunities to show their work.

Nowadays, the French government is more interested in what happened in the past. They understand that it is important to offer more care and accept that the slave trade was a crime. But since last February, everything was locked and closed. Everything stopped. Even so, society decided to make a Maron Carnival in the main streets. A maron was a fugitive slave who left the plantation and survived as form of resistance. During the Maron Carnival, people make parodic and sarcastic statements about politics, with no mask. In Martinique, the population is resistant to and distanced from the French government because of what happened after the slave trade. Now, we need a collective therapy to help understand what happened. There is trans-generational trauma in certain populations, and that trauma is massive.

AS: Let’s talk for a moment about the landscape. Glissant said, “landscape is its own monument.” Are you planning to make sculptures that respond to the landscape while you are there?

I am planning to make many sculptures as part of my journey. I plan to use different materials that I can find only in Martinique; for example, the essences of the trees and different vegetables and medical plants. I can explore the relation between the ocean and the ground.

When Césaire wrote his famous book, Cahier d'un Retour Au Pays Natal, he did not have enough money to come back to Martinique. So he went to Eastern Europe, to a small island, which he called Martinscica. He said, “Okay, that feels like Martinique.” That is where he started writing the story of colonization and the instrumentalization of the population. In Eastern Europe! It was crazy.

Think of the last paintings of Gaugin. He made images of the snow in Bretagne from memory, like a souvenir, even though he was on a Pacific island. This goes back to your question about home. Home is your imagination. My imagination fills every centimeter of my work—my movies, my sounds, my performances, my poetry.

AS: Your practice is multifaceted – art, video, music, poetry blend into one. What brings them all together?

For me, making art is an attitude, a perception in every moment of the day – and every moment is important.

I do not take touristic images. I don’t like that. When I am in Venice and I walk in the little streets, sometimes on the doors you will see a Negro figure in bronze as the knocker on the door. It is crazy and in some ways horrible, and I have many thoughts when I see such an object. But I do not take a picture. If I would like to find a picture of it, I just search on my computer. When I do decide to take an image, it is always a moment when I am sure something will happen. But you never can know what will happen. That is my idea about art.

AS: You have said that one of the outcomes of your journey will be a “Caribbean road movie” with transformed cars. Can you say a bit more about that?

Martinique does not have good public transportation. If you don’t have a car, it is impossible to get around. Everyone who is eighteen gets a drivers’ license right away. If you have a father, a mother, and two kids living in one house, you have four cars. There is a very important car culture. Cars are a kind of power, a trophy. People take care of their cars. They transform them and put decorations on them. They use massive steering wheels. They tune them up and add sound systems. Everybody needs to see you in your car, playing music. When you have these things, you are an important person. In Martinique, if you don’t have a car, you’re a nobody. So you have many old cars in the streets. The car is an important symbol for the island.

My road movie will be like a series, with different types of videos and moments. We will need to think about how and in what contexts to present the work, how to tell the story. I am not rigid about it. From an art fair to a solo show at an institution, the form would change. I think it can be interesting to play with the movie form because I like the idea of fiction. I am not making a documentary. You cannot really be objective anyway. You can only interpret—and that is the beginning of fiction. If you amplify the parameters of fiction, that can be really interesting.

AS: Every journey changes the traveler—even a traveler who is going home. How do you expect this journey to change you, as a person?

I have never done work in Martinique. If I arrive with energy, I think I will reconnect with the island. For example, right now I am afraid to speak Creole. I know that I can speak Creole, but I am afraid because I lost my accent. People there don’t like it when you lose your accent. When you lose your accent, you transform. You are no longer part of the community. People say, “you are not one of us.”

You know, the art world is difficult. It is the reason I don’t live in Martinique. I have gone very deep with my work and people have seen it, but it has taken a lot of energy. Using a lot of energy, you can lose yourself; lose your origin. You can lose your heart. And when you lose where you are from, you are nobody anymore. So, I believe reconnecting could change me.

AS: So, how are you preparing, logistically and emotionally? Some journeys are about an encounter with the unknown. This one is about re-encountering something that defines you deeply, yet perhaps in ways that you do not fully understand. This must be exciting, but also a little scary. I’m curious about your combination of feelings before you depart.

In March of 2021, when we came out of lockdown, I went back to Martinique for the first time after 10 years. I found an apartment with a garden. I did not make a big deal out of it. I had deep discussions with my mother and my father to understand some personal things in my life, to feel lighter. I did not try to meet people. I only saw my mother, my father, my grandfather and two old friends. I did nothing. I just stayed in the garden. It was important for me to just wake up and put my feet directly on the ground and reconnect with the landscape and the sounds.

It was not about art. It was very intimate. It was about reconnecting.

I am not afraid of this journey. I am very happy. The only thing I am afraid of is the calendar, because this year is very intense for me. Sometimes the stars align, and the universe says, this is going to be your massive year. And you must accept it. If I have real help and support to do the Art Journey, I can succeed. I am not afraid.

July 2021