Accra, Ghana

Coming into the continent under the cover of night, Accra slowly reveals its lights

Shining nodes of a Black Metropolis.

She stretches East and West.

Lets see how she is as a mother;

How patient and nurturing she is with the infant son.

The first leg of my journey placed me in Accra, Ghana, a town of approximately 4.5 million people located on the country’s South Eastern coast. I thought it was an appropriate place to begin my journey, because it shipped out an estimated 2 million slaves from its ports, and so, is a highly probable point from which my ancestors departed this continent. Upon arrival, I WAS reinforced in the decision as I learned how close the country held its history and how deeply the arts informed its development of a national identity, how deep an influence Diaspora Africans had on the ideological development of the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Though my journey will take me to cities in Europe, South America, the Caribbean, and the Southern U.S., Africa is what I am tracking most closely. I am not seeing this first phase of my journey as a return home—though I swore I saw a slightly taller version of my sister Christine in the central Ghanaian town of Assin Manso. This journey is an effort to understand (for myself) how West African creative principles and philosophies germinated, adapted, and spread themselves throughout the diaspora, and ultimately, the world.

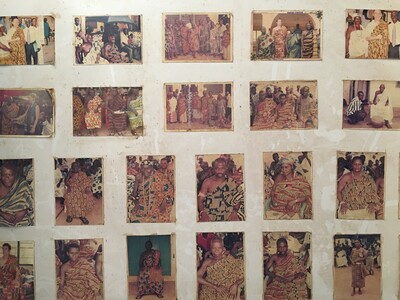

While in Ghana, I was afforded the opportunity to meet people who are well versed in the foundations of traditional Ghanaian Art, which primarily consist of products of the Asante people, a powerful sub-group of the Akan. Their creative production forms a tight network of various disciplines, historically activated as part of their religious activities. As a result, spiritual systems informed the development of oral culture, music, dance, textiles, body decoration, and sculpture.

Symbolic communication was the basis of all these disciplines.

Because these art forms were most often deployed in worship and rites of passage, formally they reflect a large degree of visual dynamism, using many variations of contrasting lines, colors, shapes, and precious or spiritually-charged materials in their creation.

Concepts are represented between disciplines: for example, the Asante proverb “the mudfish grow fat for the benefit of the crocodile” may be used in a sculpture representing the power of a chieftain, but also illustrated on the face of a flag produced by one of the area’s military units, known as Asafo. The saying itself holds multiple meanings, but mainly is a warning that serves to maintain structures of power.

More abstract examples of these kind of translations are found in the drum languages of the area.

In many Ghanaian traditions, the drum is used both as a percussion and melodic instrument. Often overlooked by many listeners is the use of pitch in African percussion instruments.

The drum can mimic elements of Ghanaian languages, of which there are 77. This opens a large range of possibilities to translate texts as symbolic rhythmic patterns.

One example of this approach, which occurred across the Atlantic, is John Coltrane’s composition, “Alabama”.

Coltrane is said to have composed this piece as a transposition of the “Eulogy for the Martyred Children” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the speech given in memoriam of the four young girls killed in the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birminghman, aka Bombingham.

Coltrane did not produce a syllabic rendition of Dr. King’s piece; rather, he worked with the cadences of Dr. King in his slow, almost chant like delivery.

Another principle of traditional Ghanaian art is reflected in how it follows the practice of creating works to mark important events, in this case, the horrific murders of innocent victims in a house of worship.

By recording, pressing into black vinyl, and distributing this art work around the world, it has become a collective occasion of mourning.

Understanding the work and gestures of artists in the diaspora through longer art historical traditions does not make these works more powerful.

Their power is intrinsic.

However, longer historical readings do create a deeper understanding and appreciation of these works, by both audiences and practitioners.

This is especially important when dealing with an art form whose intellectual foundations are under-recognized and under-appreciated.