Tehran تهران

In the Tehran Arts University library, on Enghlab Street, I meet Mojgan, the chief librarian. I don’t think I can speak freely with Firouzeh in attendance, so I ask her to wait, though this feels impolite. In Mojgan’s office, hot milk is being served in a motley assortment of cups and glasses. It is provided for all the staff at mid-morning to ward off the effects of air pollution. Mojgan offers me her ration, and I drink it, carefully tipping the cup first, so that the skin will stick to the side and not my lip. Mojgan shows me the reading rooms which have no books shelves, and the stacks. Books here must be ordered from the main desk. This is a pity, because the ordering of library shelves always yields pleasures. As Mojgan walks with me through the stacks I glimpse a short run in the music section: ‘Beethoven, Beethoven, The Bee Gees, Bon Jovi’.

I ask Mojgan if she knows of books hidden or destroyed during the 1979 revolution. No, she says, but many images were deleted. She tells me that there’s a hidden library kept in another part of Tehran that contains all the books of paintings that had to be purged of nudes after the revolution. Images of European old master paintings are currently allowed, but the copies that were defaced in 1979 are kept in case the nudes become once again inadvisable, when they can be switched for the current library copies. Prudery and lechery are very near neighbours, or maybe even twins.

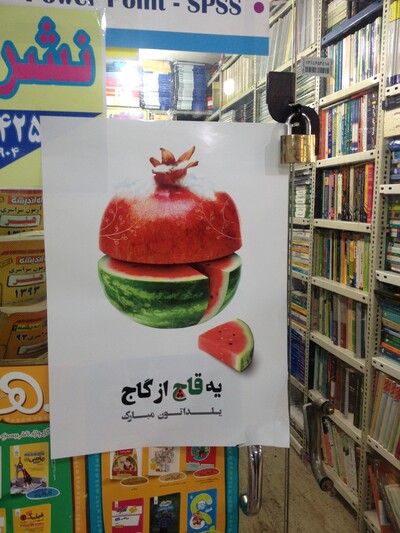

I walk Enghlab Street searching for a second-hand book of poetry by Hafez, since by all accounts he is the greatest Persian poet, though the only one I know well is Omar Khayyám. The bookshops all display posters depicting pomegranates and watermelons, wishing a happy Yalda. At Yalda, on the winter solstice, Iranian families gather at night to read together and to eat watermelon (for Spring), and Pomegranate (for winter), which relates to the Greek myth of Persephone, though they don’t speak of her. They read Persian Classics; whichever story they like best from Shahmeneh, and they use the poems of Hafez to tell their futures.

Firouzeh hands me a copy of Hafez, illustrated in a florid contemporary version of the Persian miniature, as most of them are. She tells me that after making a wish I should open the book at random. In prepared editions, the ‘omen’ (a translation of the poem’s text into an forecast of prediction) is printed at the foot of the page. I hold it and think of my son at home, and that my long journey has made him sad and fragile. I open the book, and Firouzeh translates the omen for me. “The omen is about travel!” she says. “I am far from a loved one, but my efforts will make me more professional, and will improve the future for us all.”